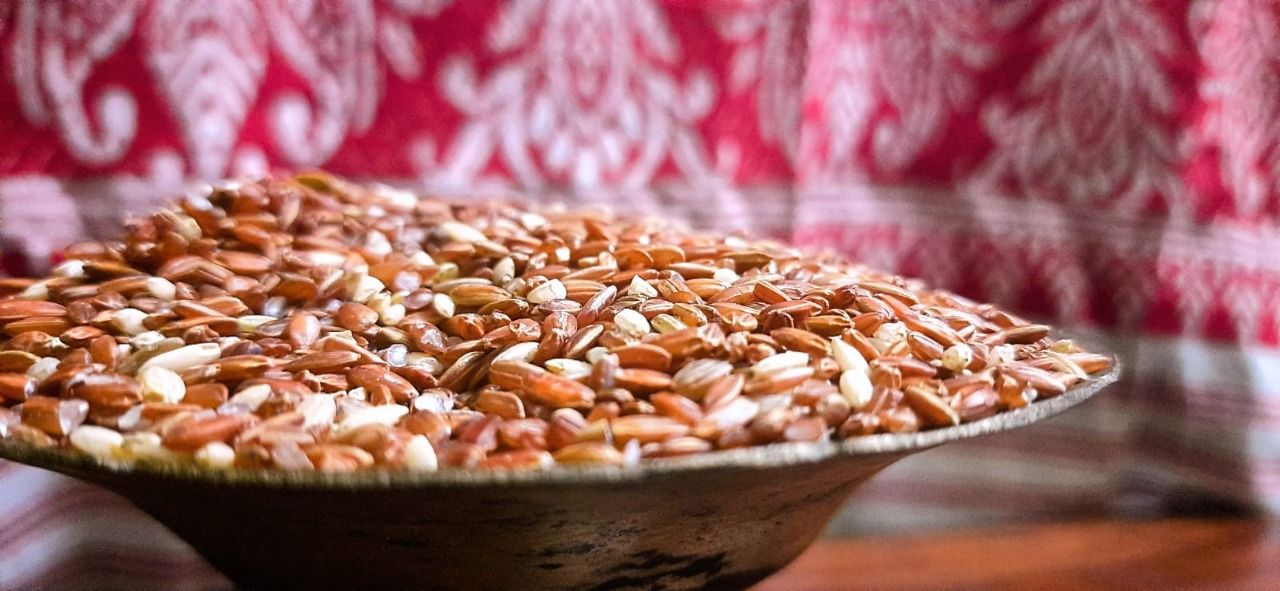

Assam’s anthocyanin-rich ‘red Bao rice’ is making a comeback as superfood

Anabil Goswami

Post On > Nov 12 2021 2415

If ever you come across an old lady in the villages of Assam, there is a good chance that she might bless you. In her blessings, she will probably say “Dhone Dhane Houk” which translates into “May you have wealth and rice!”. Such is the importance of rice in the culture of this wonderful state in the north-eastern part of India. In Assamese culture, rice plays a pivotal role, and no ritual is complete without the use of rice in some form. Over 300 varieties of rice contribute an estimated 96% of the total food grain production in the state.

In Assam, over 2.7 million families are today involved in farming and most of them are focussing on rice. Based on geo-climatic variations and the dependence on rainfall, traditionally there exists three primary rice growing seasons – Sali or winter rice, Ahu or autumn rice and Boro or summer rice. The most significant of the three remains Sali rice with over 70% of the total rice production happening in this season followed by Ahu rice and Boro rice.

Although rice production is significant in the region, it has remained largely traditional and smallholder in nature, with 97% of the farmers having less than 4 Ha of land. The production system is dependent on rainfall and often vulnerable to the ravaging floods that are typical to this region. The region witnesses abundant rainfall.

The monsoon can be both a boon as well as bane. A large portion of the cultivable land in the region is subjected to floods every year and most paddy farmers are left to the mercy of mother nature. It is in this regard that traditional deep-water rice (DWR) varieties are grown extensively in the rainfed, swampy areas.

Traditional DWR or Bao Dhan as it is known, is cultivated in over 100,000 Ha of land in Assam, especially in the flood-prone Upper Assam districts of Lakhimpur, Dhemaji, Sibsagar and Majuli. Dhemaji, the easternmost district of the state in the north bank of Brahmaputra, has over 25000 farm families dependent on DWR cultivation and offers a wide variety of Bao rice.

Sown primarily in springtime before the onset of the monsoon, DWR varieties have a long maturity period with some varieties taking as much as 300 days to mature. With the onset of the monsoons and the rains, the crops grow taller and can stay submerged. Some varieties like Bezel Bao can grow as tall as 2 m and they grow rapidly, sometimes at a pace of 25 cm per day, to compete with the increase in the water level.

Bao Dhan in general is characterised by red kernels and one of the reasons for this is the accumulation of anthocyanins. Anthocyanins act as antioxidants and are being today used in the treatment of various human conditions including chronic venous insufficiency, high blood pressure, and diabetic retinopathy. It has also been used to treat several other conditions, including colds and urinary tract infections.

Recent research also suggests that anthocyanins may help in fending off health problems like heart diseases and cancer. Apart from anthocyanins, Bao Dhan is naturally biofortified in several minerals like Iron and Zinc.

However, Bao Dhan is notorious for its low yield and one of the primary reasons why it loses its charm amongst the progressive farmers. Many farmers have shifted from this traditional practice in favour of the high yielding rice varieties – a trade-off between economic gains and nutritional properties of the food that we eat.

Today, the eating habits of people around the globe are changing. The fortunate ones who are not worrying about whether they will get their next meal are looking at what they are eating more closely. The shift from highly processed food to a nutritional alternative is evident.

In this context, the once unglamorous humble red Bao rice is gaining a lot of momentum and is right there to showcase its many advantages. What the unique variety of rice loses in terms of per hectare yield, it more than compensates in terms of per serving nutritional value. Today no supermarket or online grocery store is complete without showcasing the humble red rice in their offerings and often is priced above the more popular Basmati variety.

As the cultivation of the Bao rice is done traditionally, it is naturally organic and shields the consumer from all harmful pesticides and fertiliser residues in their food. The potential of Bao rice today is not just as a healthy alternative to the polished white rice, but also in its various other value additions that are possible.

One upcoming start-up from Assam, Bor Noi Organic, has taken an initiative to prepare both traditional preparations as well as commercial preparations like rice cookies made from Bao rice. A group of people in the district of Dhemaji are in the process of setting up a farmer producer company to prepare a wide range of products made exclusively of red Bao rice and have a focus on targeting the export market.

Several entrepreneurs from the region are today focussing on marketing and exporting red rice from the region. APEDA has formed a Rice Export Promotion Forum (REPF) and Bao rice is one of the varieties the forum is looking at. Today the Bao rice is indeed flexing its muscle and gaining momentum as a healthy food with huge market potential.

In the coming years, it will be interesting to see whether the submerged variety of rice can rise above its peers and take the centre stage as a global superfood.

* Anabil Goswami is the co-founder of Arohan Foods, India's first piggery integrator and works in the field of smallholder sustainability, food value chain and rural economy in northeast India. Views expressed in the article are his own.

** Photo by Anabil Goswami

Northeast Energy Scenario Part-1: Paradigm shift in petroproduct availability and consumption

2023-03-28 21:52:05

Consolidation of 'indigenous' votes aligned Tripura's political landscape with the rest of the northeast.

2023-02-16 14:21:53

Why Kolkata doesn’t have a Unicorn ?

2023-01-28 15:23:57

Social media literacy should be mandatory in UG curriculum

2022-11-30 17:30:53

India's new CDS, Gen Anil Chauhan has a daunting task ahead!

2022-09-30 16:04:59

Make annual BBIN summits a norm, create a common market for food and services

2022-08-13 16:09:02